In Ruby Chen's World, The Flesh Remembers What the Screen Forgets

info@hypebae.com (Hypebae) Wed, 08 Oct 2025 Hypebae

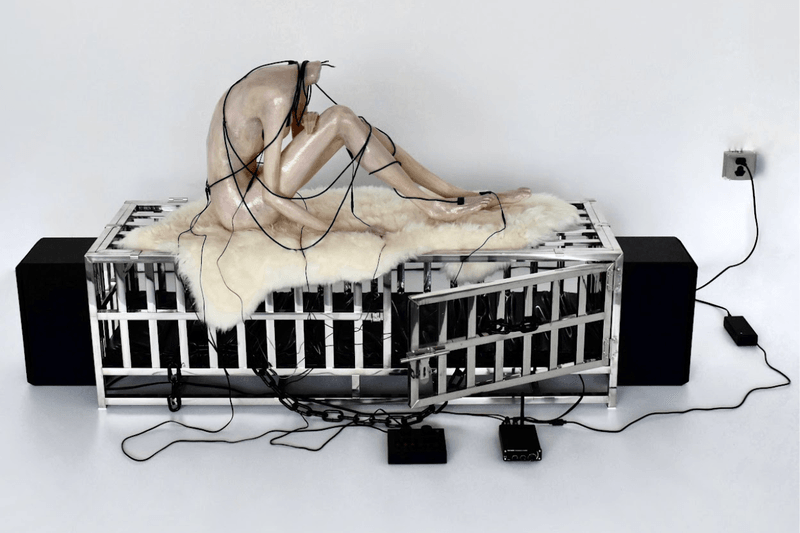

In a world increasingly mediated by screens and simulations, Ruby Chen's work feels startlingly alive. A multidisciplinary artist working across sculpture and painting, Chen explores the friction between instinct and the false promise of innovation. Her practice examines how primal desires persist within and against the systems that try to contain them, often using skin-like wax, tangled hair and pulsing sounds that echo the rhythm of the body.

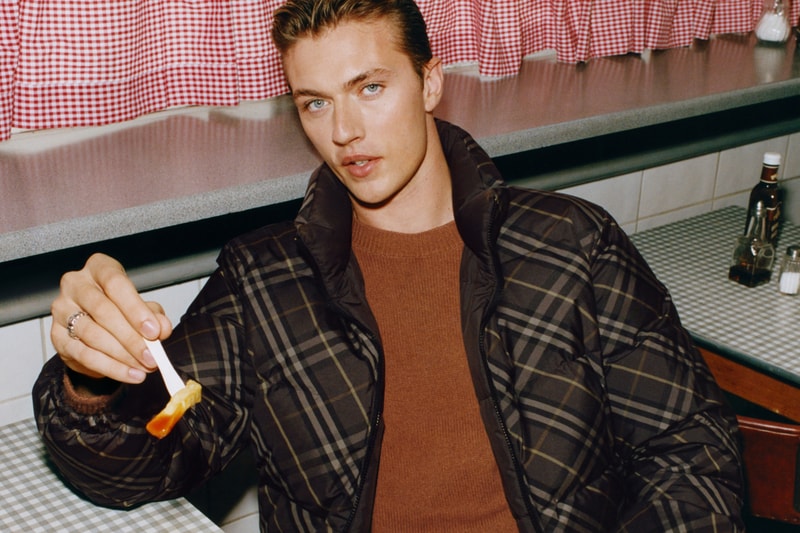

In August, Chen presented her exhibition "As It Turns Quiet, We Rot" in Shanghai. Exhibited by LUmkA, the artist questioned the conventions of "newness manipulated for consumer exploitation" with works including The Existence Outside, I Can't Save You and Cracked Skin. Now, Ruby Chen brings her work to London alongside Miles Scharff in an exhibition called "Minor Attractions" where she will showcase Paradise Lost.

View this post on Instagram

If you're London-based, check out Chen's work at "Minor Attractions" at the Mandrake Hotel, open from October 14-18.

Continue reading for our conversation with the artist about technology, neo-medievalism and the power of tenderness.

When did you first become interested in decay as a lens for understanding technology and history?

I think it began when I first came across the phrase, "revolutionaries crown themselves as kings." It made me realize how easily we tend to repeat history. Decay, to me, isn't just about things falling apart — it's about seeing what resurfaces from underneath. The decay of technology, especially, exposes how our primal impulses are simply hidden away under the mask of technological progress.

You reference technofeudalism and Neo-medievalism in this exhibition. If we're the digital serfs, what's the weirdest or most poignant form of labor you think we're already performing without realizing it?

On digital platforms, our consciousness has already become a raw material — freely given, endlessly extracted — for the benefit of the "attention economy," for the profit of tech monopolies. We pay it as tithing to exist online. Like the serfs bound to the land of their feudal lords, we're tethered to these systems, where opting out would simply mean social exile. I think that's what's really feudal about it: the fact that we are bound and tethered without even realizing.

If your sculptures could speak back to Silicon Valley, what would they say?

They'd probably sigh before speaking. I think they'd be too tired to even speak to be honest. It'd just be one long, exasperated sigh.

You explore the tension between primal impulse and the performance of innovation. How do you see our instincts shaping the way we build and mythologize technology today?

I think our instinct to innovate mirrors the same impulse to build temples and shrines — it's the desire to create meaning beyond the body. But just like old rituals, these modern acts of "innovation" are often cyclical rather than transformative. We rebuild the same hierarchies under new names, worship efficiency instead of divinity. In that sense, technology never broke from tradition, it's just a different medium to pursue our desires.

When you work with these bodily elements, what kinds of emotional or psychological reactions are you hoping they provoke in relation to technology?

Discomfort. Not in a shocking way though, but I do want to create some slight discomfort that reminds people of their bodies. Technology feels frictionless now, so I'd like to reintroduce tenderness, vulnerability, even a bit of pain. When viewers sense that unease, hopefully their body will remember something their mind had forgotten.